Selling a startup to investors

Summary

Songpark is a startup making waves in the music industry. They are building a platform where musicians play together in real-time.

The mission

Songpark was a tough sell. A first-time startup entrepreneur, asking for hundreds of thousands. For a product with no market established. My job was to build a brand that would appeal to customers and investors alike. The brand would inform the product design and pitch materials.

The outcome

Everything sprung from the narrative: Bringing musicians together. It drove our branding, our PR strategy, our pitch, and our designs.

The impact

The founder leveraged our narrative and designs to raise about 9 million NOK (north of a million AUD). A common narrative and goal now bound shareholders, the tech team, and contractors. All great. But my favorite achievement was the feedback on our investor presentation. Often, “That’s the best presentation I’ve ever seen.”

Services

- Branding

- PR strategy

- Device design

- UI design

- Pitch presentation

The challenges of building a first-of-its-kind product.

Placating the sharks

The Songpark startup is pretty clever.

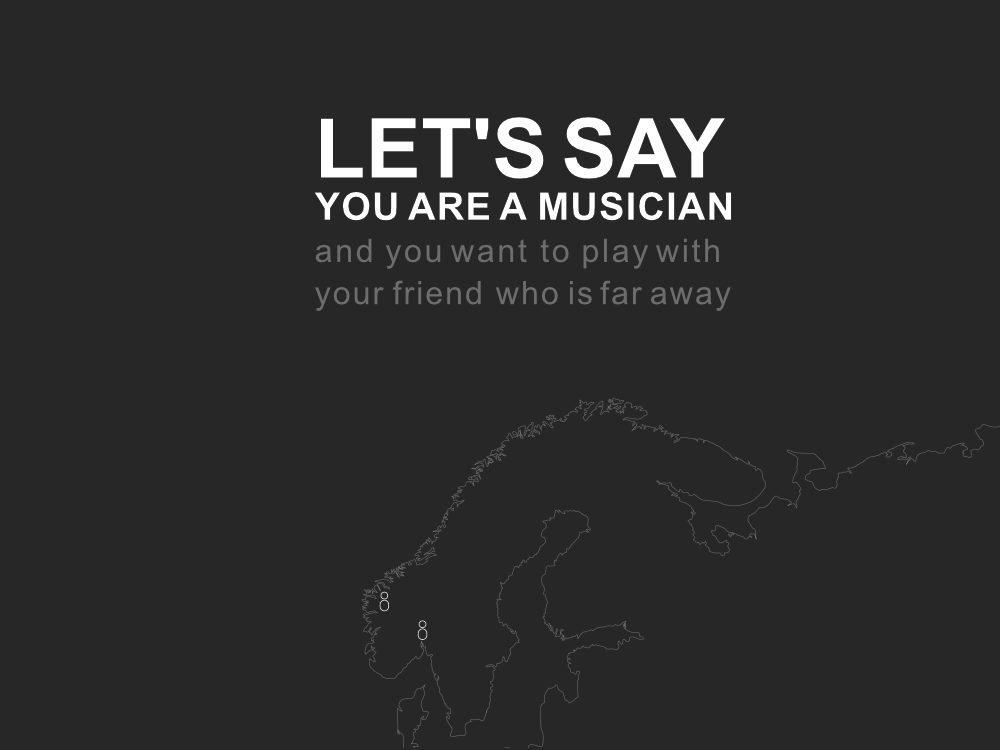

Video gamers in the 90s had to be together to play together. Then came the Internet, and they could play even when apart. Strangely, this has not happened to music. Musicians still have to be together to play together.

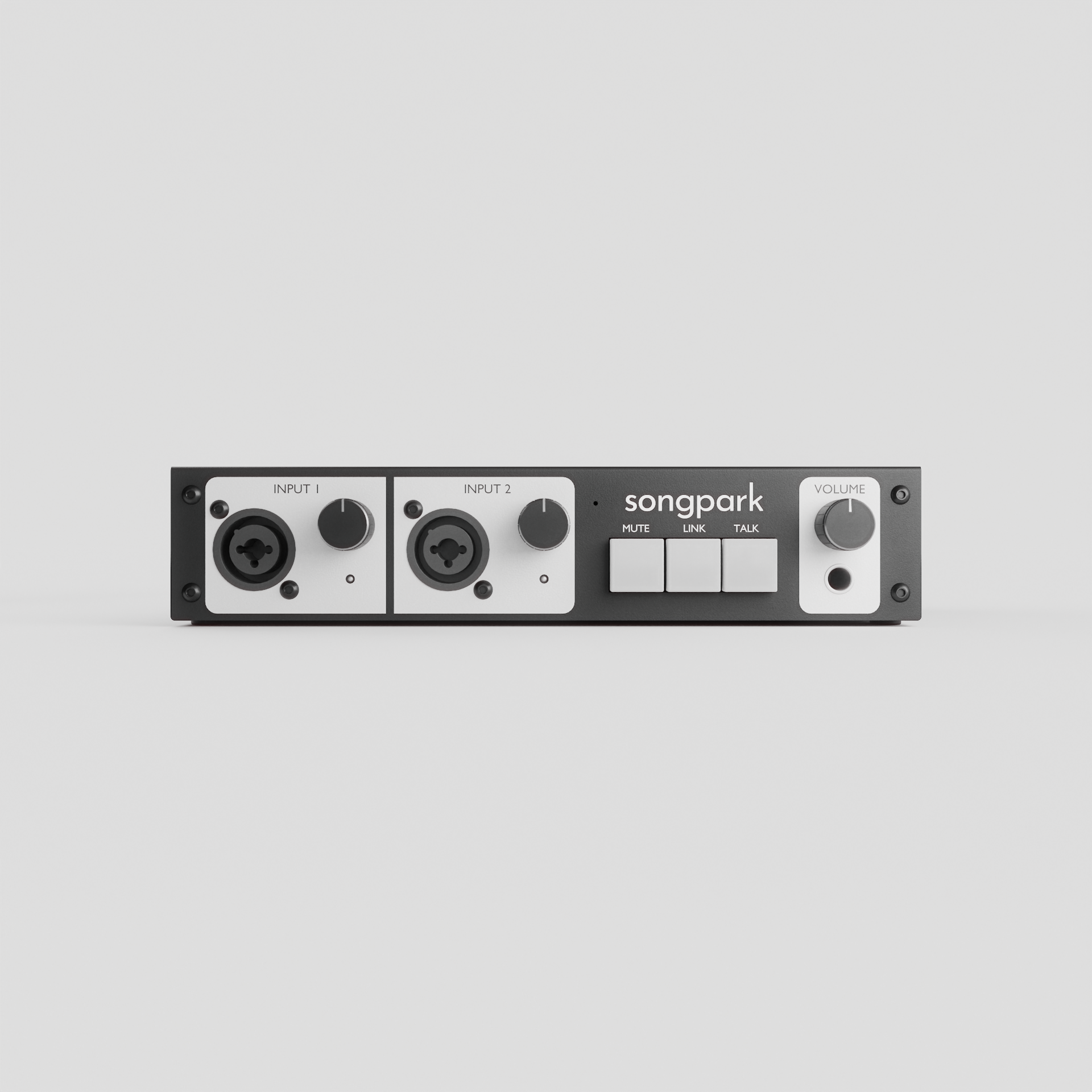

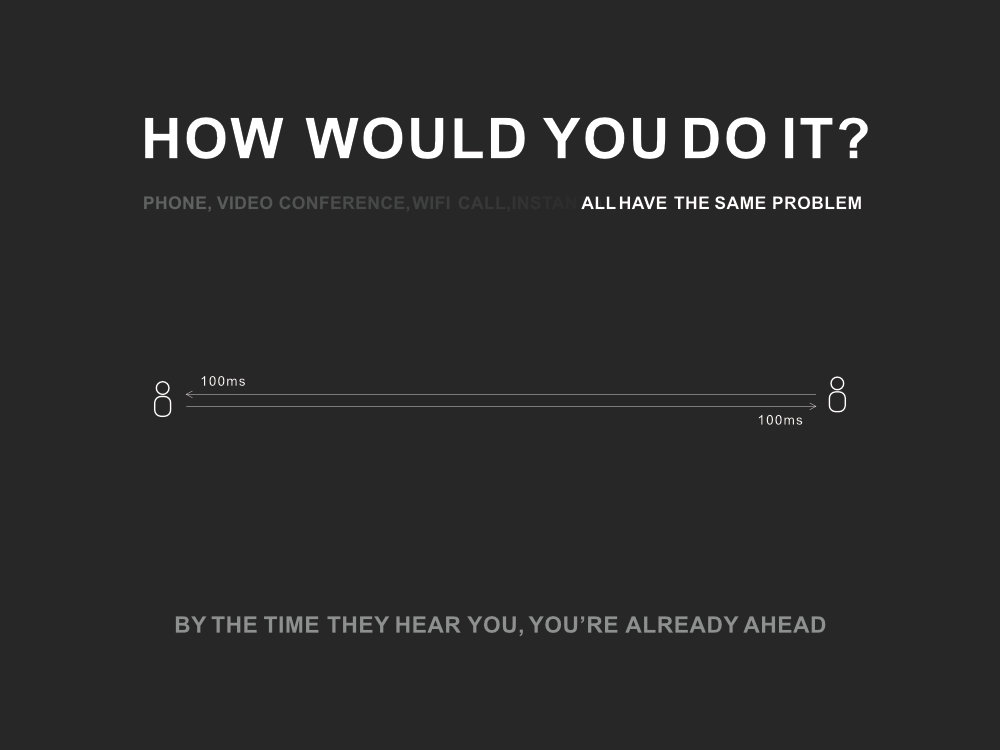

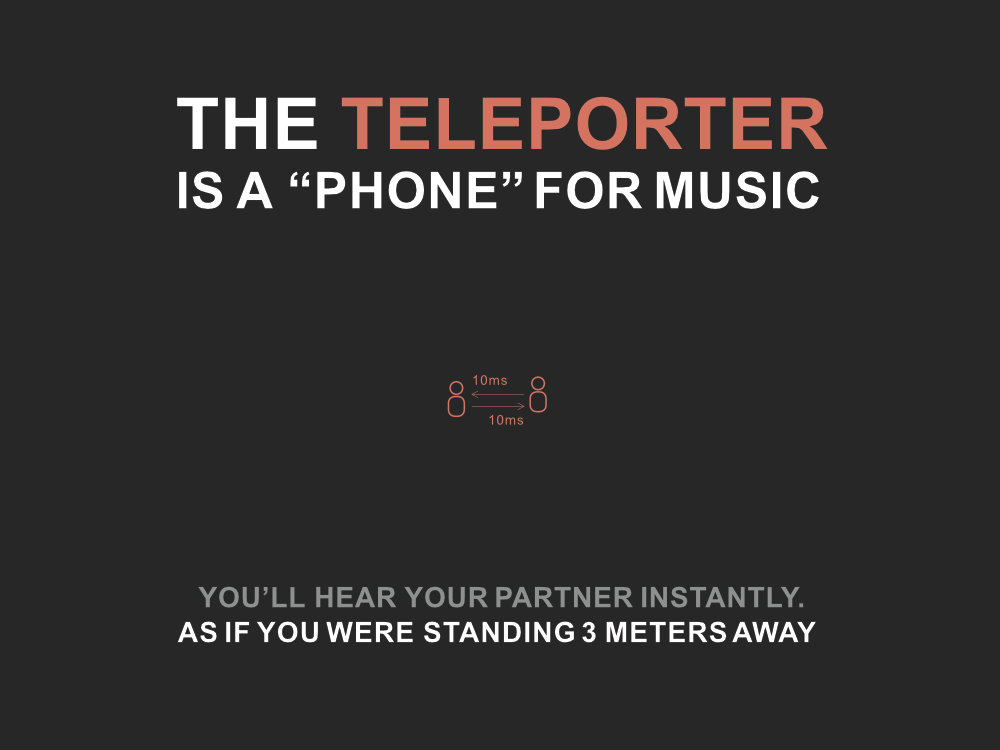

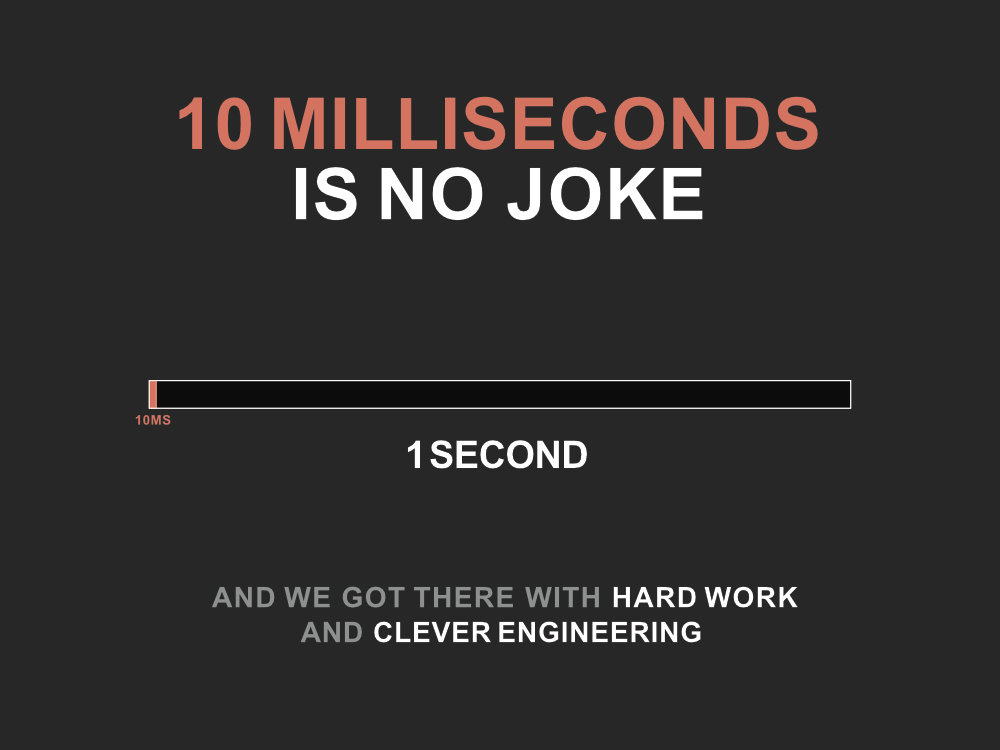

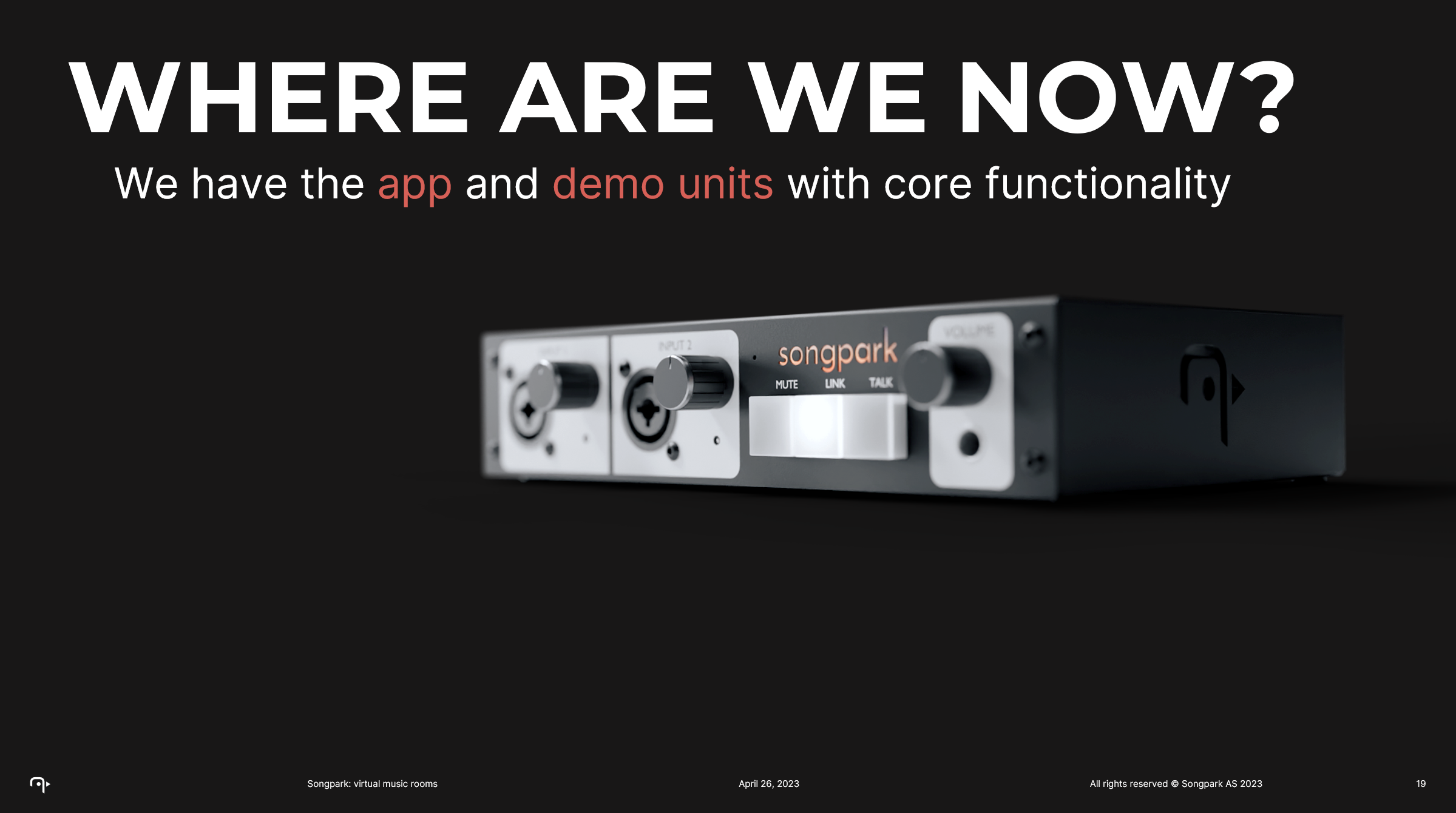

Why? Because our phones and computers are too slow. They take too long to process the sounds, so you’ll hear my drum beat a second after I’ve hit it. Our phones and computers also hesitate a little bit before playing the sound, just in case any data was lost on its way. Songpark solves these problems with a unit, the Teleporter. It processes sound lightning-fast and doesn’t hesitate.

Nothing like Songpark existed before Songpark. And that scares the investor who wants his money back. The risk-averse investor is looking for a product he has seen sold (We make high-quality ladles!) or a product that looks like one he has seen sold (It’s like Airbnb but for cars!) Songpark was neither.

Not only that, physical products are notoriously tricky to make. If a thousand things can go wrong with an app, a million things can go wrong with a unit. This made Songpark a tough sell. To outweigh the risks, we had to convince investors that this was the opportunity of a lifetime.

I am close with the founder, Christian. He brought me in to update the look of the brand, design the device, and help with the investor pitch. Christian needed material from day one, so we dove into the pool and invented water on the way down.

The persuasive power of design

Selling a vision

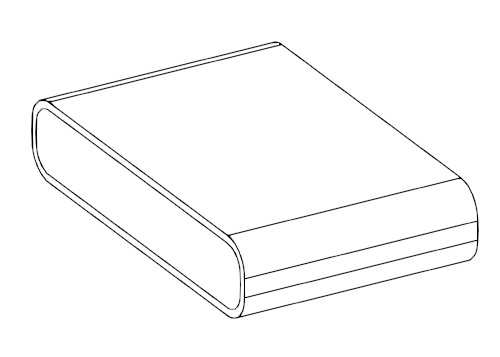

Teleporter, the musician’s "phone", drove the look of the Songpark brand. It was still under development when I designed it first. That first draft would become the “ambitious” design—the ideal. We would use it to wow investors. It had to look like pro music equipment, but simple enough that anyone could use it.

I experimented first with simple geometric shapes and found the elongated cylinder. It became the basis for the design.

The unit would eventually turn more ordinary to cut costs. These next images are in the webshop today. They’re realistic (and a little boring). I still hope the “ambitious” design will see the light of day.

Prospecting for ideas

Creativity is panning for gold. From up here, you see only the well-trodden ground. The gold is underneath. To unearth it, you must dig, then rinse. You are looking for glitter. Prospectors call it gold dust. The novice will pack his bags and bring it home, but the expert keeps digging, now around the same spot. When he finds solid flakes, he digs deeper. All the while collecting dirt and then filtering it. On his way to the vein, he finds nuggets worth keeping, which tell him that he is getting closer. When the prospector strikes solid gold he knows that he got there with systematic hard work.

Neuroscientists have mapped the brain in the act of creating. They find two nerve networks: one for divergent thinking and one for convergent thinking. You can feel them for yourself. Close your eyes and think of five non-cleaning uses for a toothbrush. Note what happens. Suggestions appear from nowhere. That’s divergent thinking. Some are mundane. Polishing cutlery. Some are outlandish. Steering a boat. Some are right in the sweet spot; creative but workable. A little torch. A conductor’s rod. Convergent thinking is picking out the good suggestions from the bad.

Here’s the rub. You can’t choose to have only the good ideas. When you’re looking for gold, you’re digging up dirt.

At this point, we’re still experimenting with design motifs. You see the gold colors, the hazy images, the tactile backgrounds, the map pattern. Some will adapt with time and stay in our designs; most will die out. That’s fine. This is the dirt-digging phase.

Visualizing value

In trading there’s a beauty: we both win. I give you money if I get more value back. Framed this way, selling is simple. We must communicate value. High value makes a high price a fair trade.

Visuals are most persuasive, as I’ve demonstrated. That's why I often start projects by visualizing the value. Drawings clarify our value proposition.

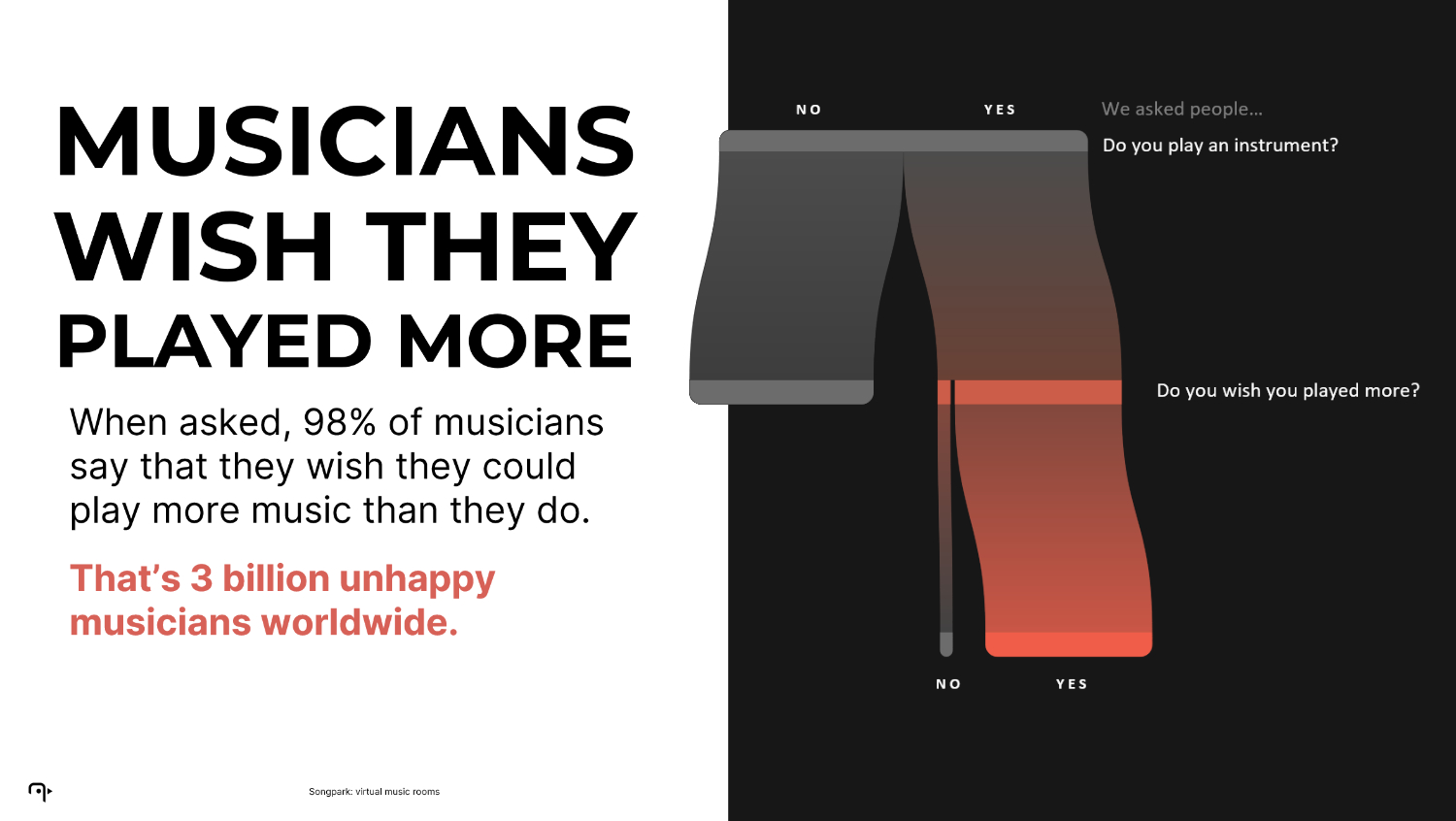

Investors want to know that people will pay for your product. Well, will they? Our market research showed that people are musical. Roughly half of us are musicians. Of those, almost everyone wishes they played more.

This image is a great start for any investor. They know that if Songpark can help people play more, we’ve got market demand.

We've got 3 billion sad musicians, most of whom have an Internet connection.

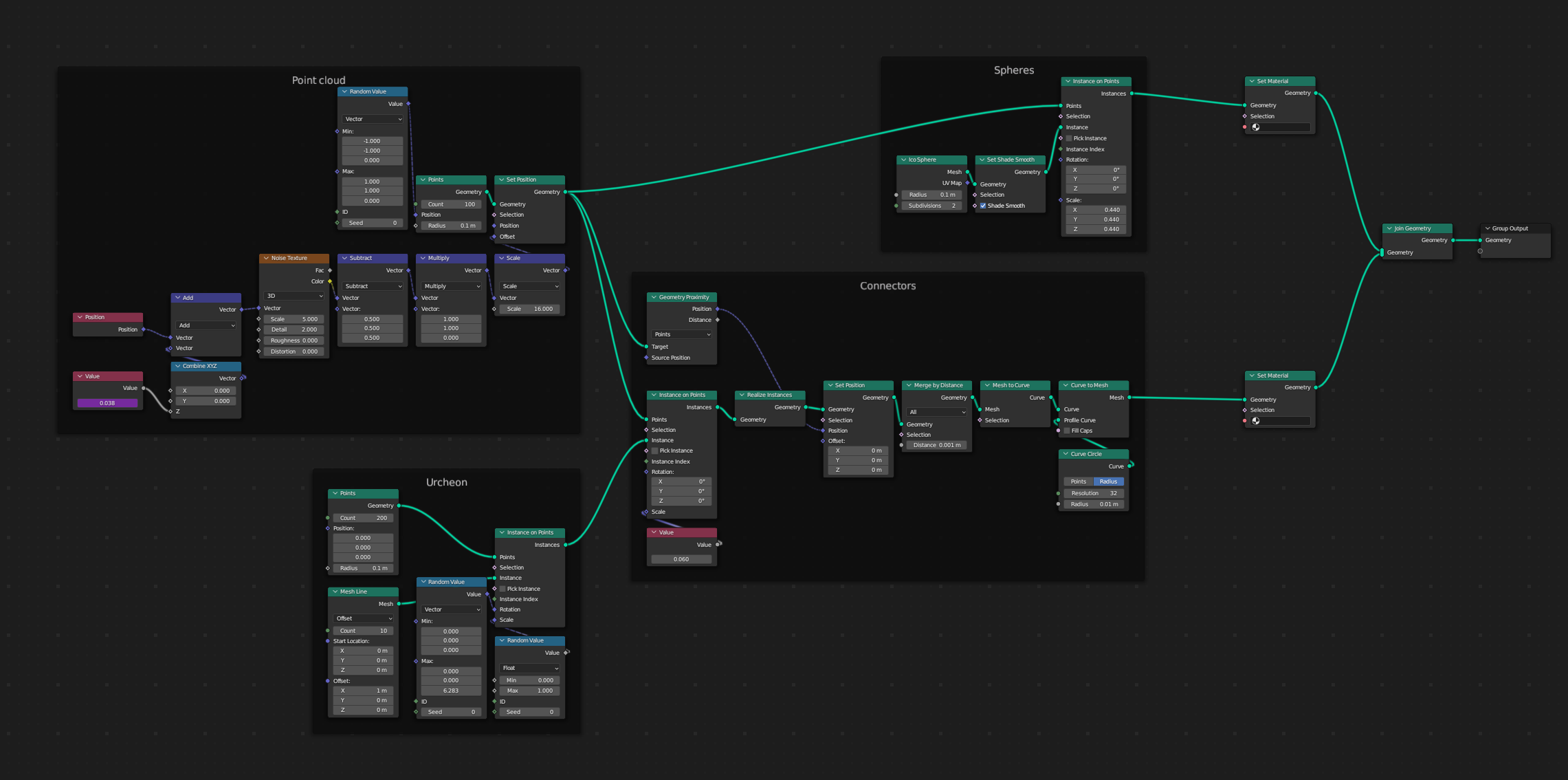

The visual R&D also led to this voronoi pattern. It describes the connectivity of Songpark users versus those outside the network. This visual is the value proposition to the user.

I made it with Blender’s procedural modeling tools. Once I’d built it, I could fine-tune the look by adjusting the number of dots, their speed, and their reach to other dots.

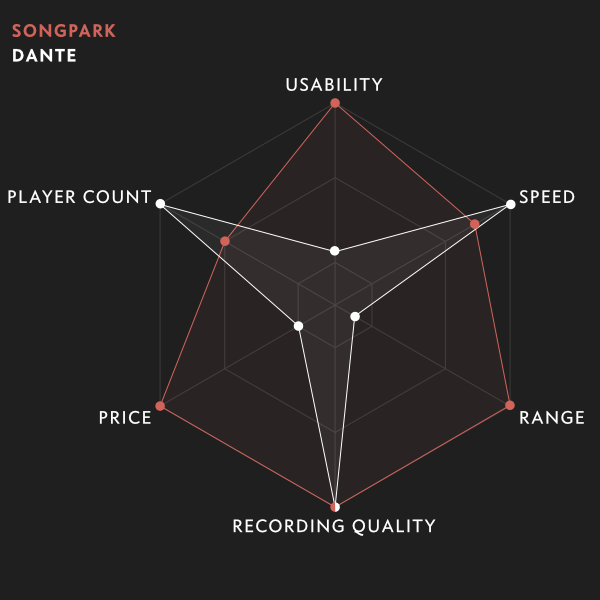

The voronoi motif resurfaces in charts, like this radar diagram. It compares Songpark to its closest competitor, Dante:

Radar diagrams are great for comparing products. By the variables you pick, you convey a message. In this diagram, I show how the companies differ. Dante is a specialty tool; Songpark is an all-around tool.

The pitch

We open our pitch with the network pattern and describe the product: Online music rooms. This formulation came from a long discussion about our place in the market. Is it a phone for musicians? Is it mainly an app? We decided on the metaphor “rehearsal rooms.” We gather here to play together. This move defines our competition. We don’t compete with apps or phones but with rehearsal rooms. And we beat them. Compared to rehearsal rooms, we are cheap, flexible, and scalable.

We had a problem: we didn’t have a problem.

Here’s what I mean… The pitch deck etiquette calls for a problem (that you can solve). Investors care about problems for a reason. People buy to solve their problems. We struggled here. Like many products, Songpark doesn’t solve a problem per se; it just makes life more convenient.

When you are in this morass, the trick is to frame it in desire. If people wish they could play more, then not playing enough is a problem. This was a key realization for us. We’ve hit a pain point for potential customers.

Here we diagnose the problem. Our claim is a simple syllogism:

3 billion people wish they could play more music.

The chief reason they don’t play more is inconvenience.

Therefore, removing barriers to play opens up a market just shy of 3 billion people.

Then we solve the problem. No travel time. Low costs. Play with anyone anywhere. This slide always seems to hit hard when we show it.

Skipping ahead a little, here comes the credibility slide. A celebrity tried the system and commented something like “No, I don’t really feel any latency.” A strategic use of italics and the quote reads like a ringing endorsement.

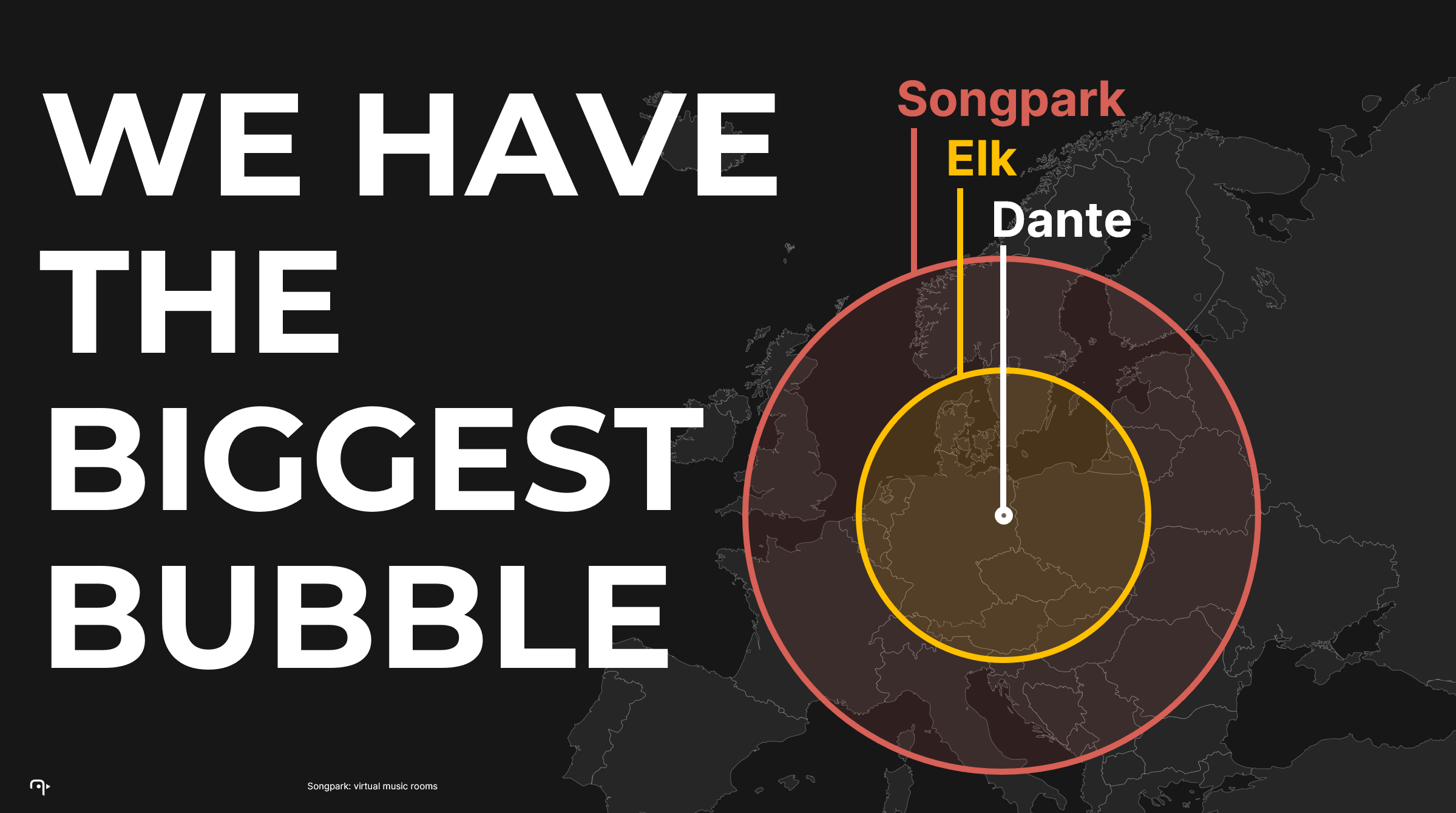

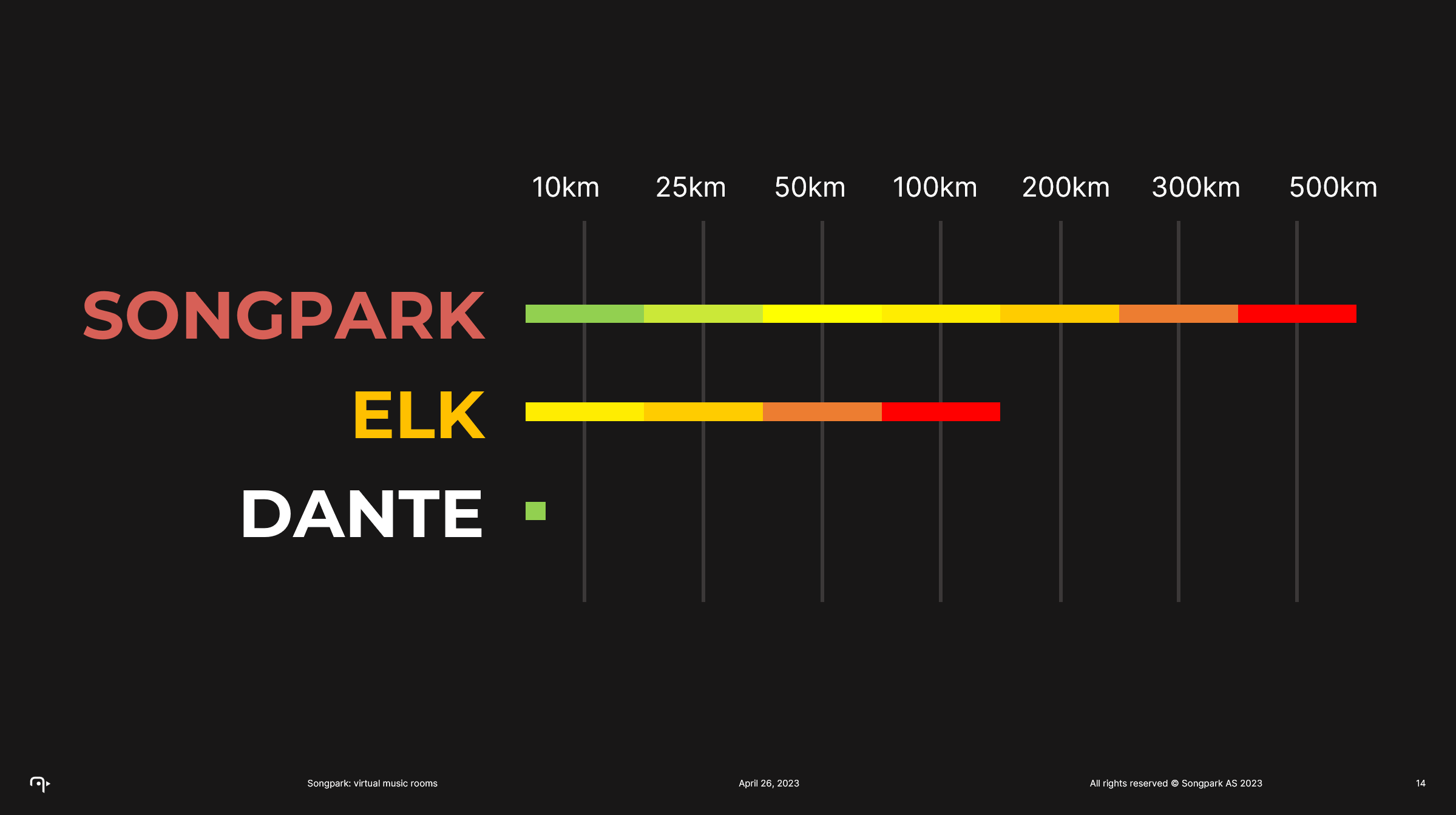

Positioning is judo. During development, a real competitor cropped up. One with a finished product and some public awareness, albeit inferior technology. We shifted our stance a bit and judo’d the trouble. Look! They’ve proven there’s a market. They’ve also proven the tech works. The quote in the slide is really about the competitor, but it applies equally to us.

If you belittle the competition, investors know you’re fooling yourself. Steel-man them. It’s the opposite of a straw-man. Build them up to the strongest version of themselves. It makes it more impressive when you still beat them.

This slide came after glorifying Elk and Dante. We show the metric that matters most: range. This is the fundamental difference between the three companies. They use three different technologies with three different ranges. UIs may change, networks may shrink or grow, but this difference will remain. Who would you invest in?

Hover over the image

These slides reassure and inspire. First: the technology is finished. There is no gamble anymore; the tech works. Second: We’re getting them out to the people soon.

At this point, we want to see dollar signs in the investors’ eyes.

How did it go?

Songpark has raised about 9 million NOK so far (north of a million AUD). That’s mainly because of the quality of the idea, the solid product, and the persuasive founder. But had he wielded a slapdash narrative, an inconsistent brand, and confusing visuals, it would have been an uphill battle.

I rest my pride on the frequent feedback on the presentation:

"That’s the best startup presentation I’ve ever seen."

Christian and I worked shoulder to shoulder, spitballing ideas and discussing our plan. We remain close and collaborate often.